10 Plane Crashes That Changed Aviation

Flying is still no easy business for many, and horror stories of airplane disasters don’t help our fears. But plane crashes help in making future flight travel safer. Here are some that changed aviation for the better.

30 June, 1956: TWA Flight 2 and United Airlines Flight 718

TWA Flight 2 took off from Los Angeles airport (LAX) for Kansas City. A few minutes later, United Airlines Flight 718 departed from LAX, bound for Chicago. TWA Flight 2 was given permission to fly at 19,000 feet above sea level; it was not allowed to go up to 21,000 feet because the United Airlines Flight was flying at that height. But because of bad weather, a request for “1000 feet on top” was granted to TWA Flight 2. At this altitude, visual flight rules (“see and be seen”) should have prevailed. However, both the airplanes were on collision course and flew into each other over the Grand Canyon. Seventy people died. As a result of the accident, $250 million was pumped into the upgrade of the air traffic control system, and the Federal Aviation Agency (now Administration) was created in 1958 to oversee air safety.

December 28, 1978: United Airlines Flight 173

In 1978, United Flight 173, which had taken off from Denver, plummeted into a wooden section of a popular suburban area of Portland. The cause? The flight ran out of fuel as it was circling the airport for an hour while the crew tried to fix a landing gear problem. It later emerged that there was breakdown of communication between the crew and the captain. Ten passengers were killed in the crash, and as a result, United revamped its cockpit training procedures around the then-new concept of Cockpit Resource Management (CRM) and the “captain is god” airline hierarchy was abandoned.

June 2, 1983: Air Canada Flight 797

A common part of in-flight announcements today is a warning to passengers that smoke detectors are fitted in the toilets. But this wasn’t always the case. Back in 1983, Air Canada 797 was headed for Quebec from Dallas, with an enroute stop at Toronto. At 7.03 pm, the cabin crew discovered a fire in the rear lavatory. Thick black smoke soon started to fill the cabin, and an emergency descent was made at Greater Cincinnati International Airport. However, the flight’s troubles were far from over. While the airport fire department was ready to tackle the flames, about 60 to 90 seconds after the exits were opened, a flash fire filled the airplane interior. 18 passengers, 3 flight attendants, the captain and the first officer made it out in time; 23 people didn’t. A fire of undetermined origin, an underestimation of fire severity, misleading fire progress information provided to the captain, and the time taken to evaluate the nature of the fire and to decide on the emergency descent were identified as likely causes.

Subsequently, aircraft lavatories had to be equipped with smoke detectors and automatic fire extinguishers. Within five years, all jetliners were retrofitted with fire-blocking layers on seat cushions and floor lighting. Further, planes built after 1988 had more flame-resistant interior materials.

August 2, 1985: Delta Air Lines Flight 191

134 people on board Delta Flight 191 met an untimely demise because of a thunderstorm. They were travelling to Los Angeles from Fort Lauderdale, with a stop at Dallas. As the flight approached for landing, it got caught in a thunderstorm, said to have more energy than 100 nuclear reactors. The pilot and first officer first spotted the lightning at 1500 feet, but it was in the descent to 800 feet that the trouble actually started. The plane started to speed up all of a sudden, before the co-pilot noticed and closed the throttles to slow it down. The Captain recognised this as the first signs of “wind shear” (explained as “a change in wind direction and speed between slightly different altitudes, especially a sudden downdraft”), and in spite of their efforts to counter the situation, the plane lost 54 knots of airspeed. It crashed a mile short of the runway, bounced across a highway, hitting a vehicle in the process and killing its driver before colliding into two huge airport water tanks.

This set off a seven-year NASA/FAA research effort which led to the installation of on-board forward-looking radar wind-shear detectors.

August 31, 1986: Aeromexico Flight 498

Aeronaves de Mexico, SA, flight 498, collided with a Piper PA-28-181 over Cerritos, California. While Flight 498 was a scheduled passenger flight, being guided by Los Angeles Terminal Radar Control Facility, the Piper airplane was flying under Visual Flight Rules (“see and avoid”) and was not in contact with any air traffic control facility. Both planes crashed into a residential neighbourhood 20 miles east of the airport; 82 people died, including 15 on the ground.

Post the tragedy, small aircrafts entering control areas were mandated to use transponders – electronic devices that broadcast position and altitude to controllers. Additionally, TCAS II collision-avoidance systems were installed, which detect potential collisions with other transponder-equipped aircraft and advise pilots to climb or dive in response.

April 28, 1988: Aloha Airlines Flight 243

An explosive decompression in Aloha Airlines Flight 243 caused a large section of the fuselage to blow off. One flight attendant was swept out of the plane in the burst of wind and died, but the rest of the travelers held on till the emergency descent was completed and got off safely, with minor injuries. The incident was blamed on a combination of corrosion and widespread fatigue damage; the aircraft had seen 89,000-plus flights. As a result, the National Aging Aircraft Research Program was initiated in 1991, which made inspection and maintenance requirements for high-use and high-cycle aircraft more stringent.

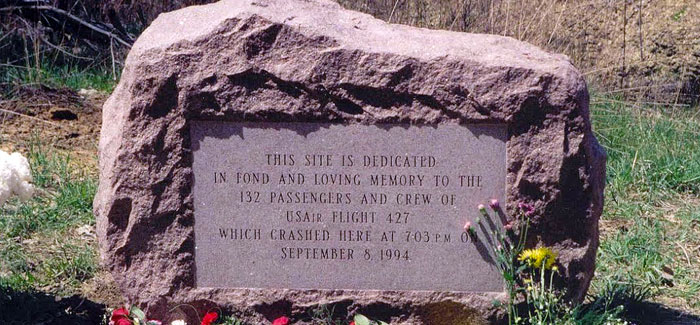

September 8, 1994: US Air Flight 427

A gruesome sight awaited those involved in rescue work when 132 people were killed in the crash of USAir Flight 427. As the flight began its approach to land at Pittsburgh, the Boeing 737 suddenly rolled to the left and plunged 5000 feet to the ground. The National Transportation Safety Board determined that the probable cause was a loss of control of the airplane resulting from the movement of the rudder surface to its blowdown limit. A jammed valve in the rudder-control system had caused the rudder to reverse, making it go left as the pilots frantically pressed on the right pedal.

Boeing, which initially tried to blame the crew, later spent $500 million to retrofit all 2800 of their flights. Congress passed the Aviation Disaster Family Assistance Act, which transferred survivor services to the NTSB.

May 11, 1996: ValuJet Flight 592

In 1996, ValuJet Flight 592 crashed into the Everglades near Miami, killing 110 people. The cause was that one of the chemical oxygen generators in the cargo caught fire because of a bump. The pilots were not able to land the flight in time to avert the disaster. Later, FAA said that ValuJet, a discount airline, was not authorized to carry oxygen generators. In the aftermath, the agency mandated smoke detectors and automatic fire extinguishers in the cargo holds of all commercial airliners. It also bolstered rules against carrying hazardous cargo on aircrafts.

July 17, 1996: TWA Flight 800

When Paris-bound TWA Flight 800 exploded in mid-air near the coast of Long Island, killing all 230 people on board, the initial cause was thought to be an act of terrorism. After reassembling the wreckage, the NTSB determined that an explosion of the nearly empty centre wing fuel tank (CWT) was the culprit, most likely after a short circuit in a wire bundle led to a spark in the fuel gauge sensor.

Actions taken since the disaster have included changes to reduce sparks from faulty wiring and other sources. Boeing developed a fuel-inserting system that injects nitrogen gas into fuel tanks to reduce the chance of explosions.

September 2, 1998: Swissair Flight 111

There were 229 casualties – everyone on board – when Swissair Flight 111 crashed into the Atlantic, about 5 miles off the Nova Scotia Coast. The flight was bound for Geneva from New York, and an hour into takeoff, the pilots smelled smoke in the cockpit. An emergency descent was embarked upon, but the fire was quicker in its spread and cockpit lights and instruments failed. The search for the cause of the fire took over four years; it was eventually cited as electrically stoked and was traced to the plane’s in-flight entertainment network, whose installation led to arcing in susceptible Kapton wires above the cockpit. The flammable Mylar fuselage insulation too was an easy victim. Later, Mylar insulation was to be replaced with fire-resistant materials in about 700 McDonnell Douglas jets.