Snakes and Ladder – an Indian-origin ancient board game

What’s the most popular game that you see kids playing these days? PlayStation, Minecraft, and a variety of RPG (role-playing games) have captivated kids of this generation. On top of that, mobile accessibility has enabled them to play games whenever they want to; hence, it wouldn’t be wrong to assume that millennials would not know the value of old-fashioned board games.

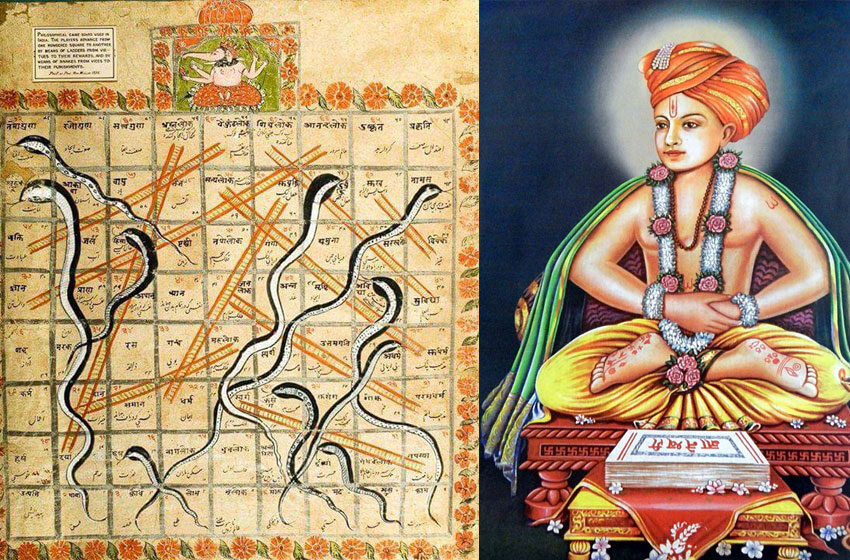

Friends or family members gathering together to play a game of chess, ludo, or snake and ladder has become a thing of the past. Speaking of which, did you know that the snake and ladder’s origin can be traced back to the 13th century AD? Poet saint Swami Gyandev created a children’s board game called ‘’Moksha Patam”.

How did snake and ladder come into existence?

13th-century poet Swami Gyandev invented the board game to teach children about morality, ‘’karma and kama’’ which relates to destiny and desire. Besides, if old records are to be believed, the game originally had more snakes and fewer ladders as the prevailing belief was that the path to reach moksha is riddled with difficulties. Also, while traversing through life, an individual would face temptations and evil (as indicated by snakes), and failing to control oneself can lead to despair or death.

Furthermore, boxes used to have different symbols that symbolised either evil or virtue; in the original game, the squares of virtue are Faith (12), Reliability (51), Generosity (57), Knowledge (76), and Asceticism (78). The squares of vice or evil are Disobedience (41), Vanity (44), Vulgarity (49), Theft (52), Lying (58), Drunkenness (62), Debt (69), Murder (73), Rage (84), Greed (92), Pride (95), and Lust (99).

Over time the game’s popularity rose and found its presence in the Islamic world in the form of ‘’ ‘’shatranj-al-urafa’’ in parts of India, Iran, and Turkey. Besides, the Islamic version is based on Sufi philosophy, wherein the game symbolises the dervish’s quest to leave behind the trappings of worldly life and achieve union with God.

On a similar note, Mokshapatam gameplay did not end with the square hundred but one that people could play over and over until they reached Vaikuntha (the sacred domain of Vishnu) after journeying through many rebirths and corresponding human experiences.

Westernisation of the ancient snake and ladder game

When the ancient board game was brought to England, the toymakers replaced the Indian virtues and vices with English ones to indicate Victorian doctrines of morality. For instance, it had squares of Fulfilment, Grace and Success were accessible by ladders of Thrift, Penitence and Industry and snakes of Indulgence, Disobedience and Indolence caused one to end up in Illness, Disgrace and Poverty.

However, much earlier, when Frederick Henry Ayres, the famous toymaker from Aldgate, London, patented the game in 1892, the squares of the game board had lost their moral connotations. There were earlier examples in Victorian England and mainland Europe that had a very Christian morality encoded into the boards but the game actually originated in India as “Gyan Chaupar”.

Victorian versions of the game include the “Kismet” board game (ca 1895) now in the Victoria and Albert Museum’s collection. There were other similar games such as “Virtue Rewarded” and “Vice Punished” (1818) and the “New Game of Human Life” (1790) although the latter did not contain snakes and ladders on its board.

Moreover, it is important to note a British official named Richard Johnson’s account; although he was a competent administrator, he made quite a fortune through corruption. He actively participated in Warren Hasting’s infamous looting of the Begums of Oudh. Johnson was also an eclectic collector and commissioned work by many Indian artists and scholars of which 64 albums of paintings (over 1,000 individual items) and an estimated 1,000 manuscripts in Persian, Arabic, Turkish, Urdu, Sanskrit, Bengali, Panjabi, Hindi and Assamese form the “backbone of the East India Company library”

Amongst his collections, he had the ‘’Gyan Chaupar’’ board in his possession a hundred years before the game was imported to the west and transformed into a racing game.

Despite, the advanced technology that has revolutionised games, a simple board game of snake and ladder stood the test of time.